By Mark D. Steckbeck and Roger H. Schmelzer

There is growing interest among insurance regulators in finding market driven solutions to address the problems of troubled companies. Regulators are showing less interest in placing troubled insurers into liquidation, and troubled insurance companies seem to present investment opportunities for the capital markets.

These propositions were central to an in-depth series of panel discussions on capital markets investment opportunities at “Emerging Investment Opportunities: Bridging the Gap between the Capital Markets and Troubled Companies” hosted by the International Association of Insurance Receivers (IAIR) in October 2007. The one-day program explored the potential use of funding from the capital markets to address some of the issues and potential solutions to the serious financial challenges facing troubled insurance companies.

The program included insurance commissioners, reinsurers, attorneys and investment experts from the U.S. and abroad. The panels offered insights into the possible use of investment capital to assist regulators in their efforts to rehabilitate or runoff troubled insurers; it also reviewed the restructuring mechanisms available in other countries. In addition, the program examined some of the critical considerations and impediments potentially associated with these challenging investment opportunities. This paper summarizes highlights from these discussions.

Capital Market Opportunities in Troubled Insurance Companies. The first panel of speakers (Christopher Flowers of J.C. Flowers & Company, New York Insurance Superintendent Eric Dinallo and Forrest Krutter of Berkshire Hathaway) examined some of the issues and opportunities for investing in troubled insurance companies in the segment.

Flowers observed that while there is a growing appetite for investment opportunities, special challenges face potential investors in property and casualty liabilities, chiefly the need for adequate potential returns to interest investors.

There must be reasonable predictability of the investment returns, explained Flowers, adding this is something that is difficult to achieve with property and casualty claims in general, but especially so with the involvement of asbestos and environmental claims and natural disasters. Flowers went on to explain additional uncertainty is found where key assumptions used to evaluate company liabilities can be unexpectedly changed, for example, re-opening the statute of limitations on previously expired tort claims.

Another challenge facing investors is the high cost of collateral. Collateral posted by investors to cover property and casualty liabilities must be invested safely, which may limit the investor to relatively safe but modest investments. To an institutional investor seeking returns in the range of 20 percent, a five percent return on a treasury note is significantly below his required return threshold.

Structural Impediments Facing U.S. Investors. The second panel examined some of the structural impediments facing U.S. investors that are different from those faced by investors in troubled companies in Great Britain. The panel included Paul Dassenko, of azuRe Advisors, Inc., Oliver Horbelt formerly of Centre Group of Companies, Richard Whatton of Independent Services Group and Tim Graham, LaSalle Re.

Although both systems recognized the importance of making timely payments to policyholders and claimants, the comparison generally stopped there. While the U.S. system strongly favors policyholder protection, the British system would seek ways to bring finality to a company’s affairs, including its liabilities, thereby allowing investors to salvage part of their investment, and if possible, return at least some portion of their capital to the market.

For an institutional investor seeking an investment opportunity, the U.S. system creates several barriers. First and foremost, investors want to make money. With no benchmark for success acceptable to the regulators, investors may not be interested.

Second, there is a general lack of quality information to enable investors to evaluate troubled insurance companies. Additionally, there are a number of pitfalls for investors. These include a lack of understanding of the liability side of policy risks. Investors want to be able to extract their money quickly to pursue other investment opportunities. This may not be possible where the company has long tail exposures. Investors would want to accelerate liabilities in order to outrun adverse development. However, this approach would run contrary to the U.S. system’s strong preference for placing the interests of policyholders and claimants above the interests of investors.

Evaluating the Investment. In “Straight Talk from the Street,” the third panel addressed some of the key factors used by private equity investors when evaluating private investment deals. The panel included Bart Zanelli of Guy Carpenter, David Platter of Credit Suisse, Martin Alderson Smith of The Blackstone Group and Bill Goddard of Bingham McCutchen.

Time horizon. Private investors seek investments with a three to six year exit strategy. This strategy is at odds with the long-tail nature of property and casualty liabilities.

- Potential rate of return. Equity investors are seeking investments that offer solid returns in the range of 20 percent for investment in a healthy company. To offset the greater risks associated with investment in a troubled company, investors may require expected returns as high as 30 percent. Returns of this magnitude may not be either achievable or politically palatable where a company is in the hands of a regulator and other creditors are receiving cents on the dollar. Investors are also concerned about reputation risk when they participate in deals that might draw damaging criticism.

- Time and money required to close a deal. The longer it takes to close a transaction and the more money that must be spent, the less attractive the deal. This might occur where regulators are required to address objections or offer public hearings before approval is granted.

- Difficulty in quantifying the level of investment risk. As the risk becomes less quantifiable, investors require greater returns or they will look for other opportunities. Finally, investors want to maintain at least an adequate level of control over the risks affecting the return on investment. Given the unpredictable nature of asbestos and environmental claims, natural disasters, and the ever-changing legal environment, it remains a challenge to control the risk factors affecting investment returns.

The panel examined how investors and regulators could close the gap on some of these obstacles. Four key elements to success were identified: the first issue is transparency. Parties must identify all issues and problems and exchange information to permit full evaluation of the transaction. Next, parties must have an open dialogue. The parties must identify and address all transactional elements including taking care of policyholder concerns and the investor’s profit expectations. Third, the value proposition for the transaction must be identified: all reasons for the company’s distress must be disclosed and all constituents must be represented at the bargaining table. Fourth, individual egos and private agendas must take a back seat to the transaction’s success.

Additional challenges facing potential investors include a poor institutional memory of the target company. By the time the trouble company is entertaining potential investors, many of its more experienced and knowledgeable employees have already departed. Another challenge is the inability to quickly access good quality information regarding the company’s operations and financial condition. There are also fragmented demands being made upon the company or the regulator from multiple constituents. Managing and reconciling these demands with regulatory imperatives while attempting to structure an investment deal adds another layer of complexity and cost. Moreover, there is no organized secondary market for the sale of troubled insurance companies. Without an established market, the transaction costs are higher. Finally, parties to the transaction must deal with fragmented claims. Stakeholders with competing interests each seek individual relief. Parties must find fair and effective ways to address these interests in order for the deal to proceed.

Regulatory Issues. The regulatory panel included Commissioner Al Gross of Virginia, Commissioner Thomas E. Hampton of D.C., Director Michael McRaith of Illinois, Deputy Commissioner Michael L. Vild of Delaware and Peter Gallanis, President of the National Association of Life & Health Insurance Guaranty Associations.

Mr. Gross stated his belief that insurance company receiverships should be managed with four principles in mind. First, policyholders have the right to have their claims paid timely and in accordance with their insurance contracts. Second, policyholders have the right to be protected against market abuses, for example, they should retain the protections that were granted by the state’s unfair claims settlement practices act. Third, claimants must be treated equitably. Fourth, the receiver is responsible for maximizing the value of the estate for the benefit of policyholders and other claimants.

Director McRaith believed that states are doing a better job of monitoring the financial condition of companies. He believed that if properly supervised, runoffs can benefit customers by avoiding some of the frictional costs of liquidation.

Deputy Commissioner Vild spoke of the desirability of early intervention on the part of regulators. He believed that the desired three to six year ideal investment horizon may not always be available and stated that he would be receptive to seeing proposals that addressed the issue of the investor’s withdrawal strategy up front. He further emphasized the need for transparency and full disclosure.

What Does the Future Hold? The final panel consisted of Howard Mills, Deloitte & Touche USA (and former New York Superintendent of Insurance), Nigel Montgomery, Sidley Austin and Chris Stroup, Wilton Re. The panel was asked if members expected to see an increased level of interest in investing in troubled companies by the capital markets. After summarizing some of the comments and themes voiced by the earlier panels, the presenters stated that the primary goal must be to protect consumers while still offering opportunities for investment of capital.

There is no one-size-fits-all approach to addressing the problems with troubled companies. Each company is unique and must be evaluated on its own merits. On the balance, however, the panel members did not expect to see a high level of interest by the capital markets in making investments in insurance company rehabilitations. For the capital markets to be interested in investing in troubled insurers, the insurance industry must be able to end runoffs within a reasonable timeframe.

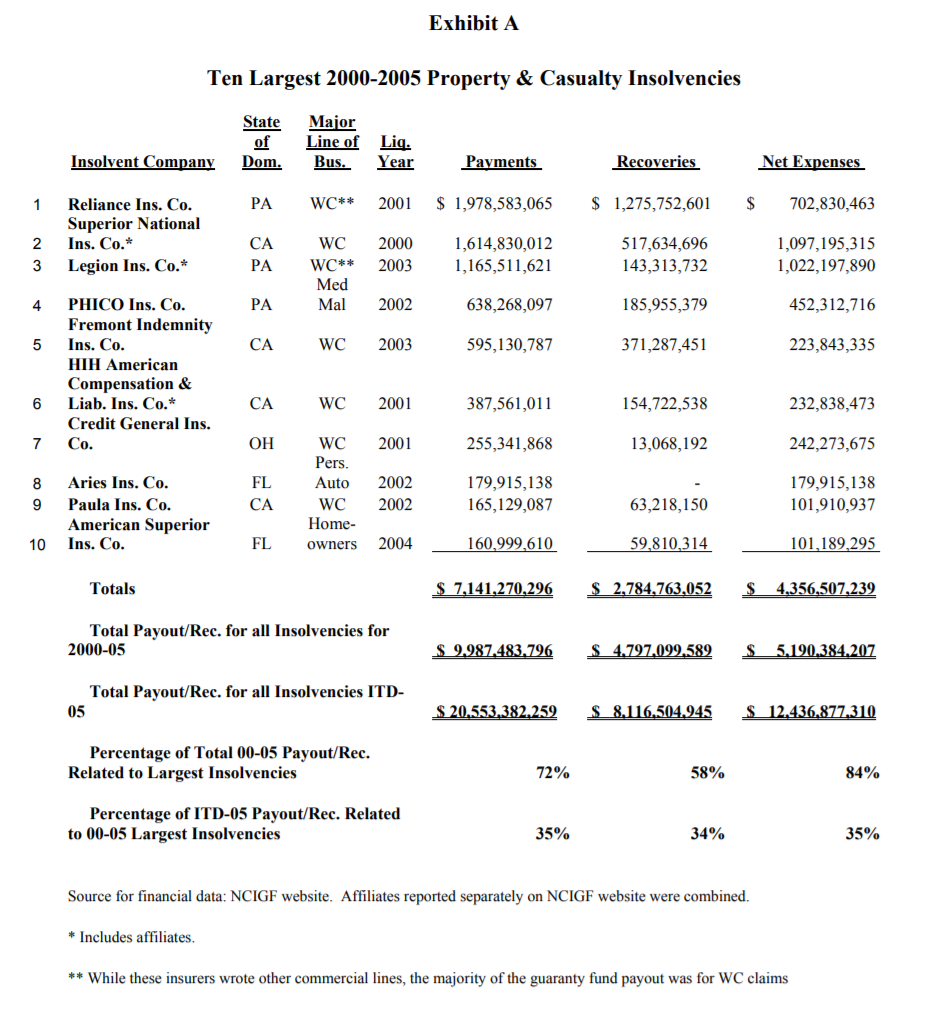

NCIGF Analysis. The NCIGF suggests that the primary purpose of any alternative approach to insolvency be protection of the public from financial loss.

The state-based property and casualty guaranty fund system affords covered claimants a statutory remedy in the event of insolvency – many claims of the average consumer are paid in full. Based on existing state liquidation statutes and priority distribution laws, the needs of consumers, who are generally unsophisticated in insurance matters, are placed ahead of nonpolicyholder claimants and everyone with the same level or type of claim is treated equally.

It is imperative to know how and to what extent fundamental consumer protections would be affected under any alternative to outright liquidation. Would policy claims be reduced below their contract value in certain scenarios without the consent of claimants? Would consumers still receive timely payments, the full benefit of their insurance contract, fair treatment in the claims settlement process and availability of a meaningful claims appeal process? All of these are protections afforded in a traditional liquidation administered under existing state law. If they are not maintained, exactly what is the public policy objective in support of such a change?

Property and casualty insurance is a necessary ingredient to development of a civilized society by impacting the ability of commerce to develop and flourish within a free market economy. It is a contractually specified and validated agreement to transfer risks tied to virtually all personal and business investment decisions. This in turn allows individuals and businesses to confidently manage their risk and make investments, important actions that spur economic growth.

Legislators and regulators have already established the guaranty fund system to make good on the insurance promises of failed property and casualty companies by providing at least a partial remedy for insurer insolvency. That remedy retains the sanctity of the insurance contract by affording a measure of protection to those claimants state legislatures have deemed most in need of protection. Any decision to modify the existing level of consumer protection should be undertaken with the utmost of thought and deliberation.